|

|

Indians of Milton The world for this writer, when a boy, consisted mainly of East Milton. All places where I had played were there. My schools were there. The friends I knew, the faces I saw year upon year, all came from there. That is, until I entered Cunningham Junior High, where I met other early teens from a whole 'nuther part of town, with which I had only scant, fragmented familiarity. Now the world for me consisted of two entities: East Milton; and that other, more foreign part of town. What particularly interested me in meeting kids from west of East Milton were stories they told about finding Indian arrow heads and even Indian huts in the woods of that hinter region. Whether the stories were true is another matter. (It is highly improbable, after all, that crude, 19th-century huts could have survived so many decades in nature. And if some had, certainly the world would have known of it from sources historically more reliable than seventh-graders.) But even if the stories were only exaggerations of adolescents, being swallowed whole by other adolescents like myself, they nonetheless captivated youthful imagination and fancy. Those old tales came to mind again, and even gained some measure of plausibility, upon finding an 1898 article by preeminent Milton historian, A. K. Teele, enticingly called "Indian Graves in Milton.” It was referencing a discovery made, of course, on that other — that western — side of town. While that discovery would be fascinating enough, Teele further noted a "peculiarity" in the graves’ having been "placed side by side ranging east to west." "According to the natural topography of the land," he observed, "we should expect the graves to run north and south." Hence he speculated whether this contrary configuration may "have been the Indian usage, or religious sentiment, to bury their dead with the head facing east, disregarding all other considerations." Considering that early settlers in more isolated areas would bury kin on their own land, the historian said he knew "of but two houses standing on that side of Canton avenue" in 1700s: One was Ebenezer Sumner’s, “doubtless the first house built in that section of the town.” The other, “the house of Mingo, an Indian, one of the Ponkapog [sic] tribe, was there in 1763, and probably several years earlier.” Assuming the antiquated excavations were Native American graves, Teele concluded they probably belonged to family members of Mingo, a very aged Ponkapoag still living in 1763 – even though the excavations were at “some distance” from Mingo’s house, and separated from his lot by two walls dating at least from the beginning of the 18th century. We have no report that they were ever examined for bones or artifacts, and subsequent development of the area doesn’t seem to have safeguarded them. So, there is only their ritualistic-like arrangement cited by Rev. Teele to indicate these were graves, Indian or otherwise. He himself noted: “But in the opinion of a missionary of long standing among the Indians, who is considered good Indian authority ... these smaller excavations may have been ‘Dry Ovens’ for cooking and preparing of material for their religious ceremonies; or more probably ‘Steaming Pits’ for steaming themselves to get rid of severe colds or worse diseases. This was common among the Indians of New England.” For, while that would not explain their unlikely orientation in the hillside, also found in the same area were other, somewhat larger, if less distinguishable pits with charcoal bits and rocks that appeared discolored from fire. It was speculated that these larger pits were used for tanning skins. Teele adds that all over the same field, where the presumed graves were discovered in 1898, were “signs of the disturbance of the soil in periods long past.” Also, as further evidence that the area had been occupied and even populated by Native Americans, the nearby hill on which the new high school and the Indian Cliffs homes now stand was once called “Wigwam Hill.” Last of the Ponkapoags

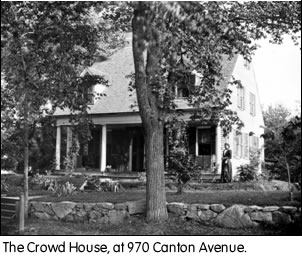

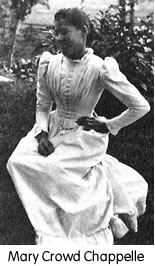

When Mary died at age 91, in 1916, she was buried in the Crowd family lot in Milton Cemetery, on Lilac Path, survived by only three of her eight children. One of these was a daughter also named Mary, who in 1896 married George Chappelle. The Chappelles lived in the 970 Canton Avenue house that Daniel Crowd had bought in 1860, and Mary Chappelle continued to live there, after her husband abandoned her, until her death at age 67 in 1933. Upon Mary Chappelle’s death the largely obscure, but irrefutable public record of Ponkapoags in Milton’s western side comes to a close. Meanwhile, for us mildly envious East Miltonians – save for Native Americans in the early 1600s with whom Richard Collicot and John Holman traded fur just off of today’s Adams Street – there was otherwise little such romantic Indian lore to boast of in our history. That is, until the arrival of the very colorful Dennis “Dennie” Meuse. Dennie was a full-blooded Native American – just not one who had been native to our town or, for that matter, to our national boundaries. For Dennie was a member of the Micmacs, a tribe of the Canadian Maritimes and northern Maine. The name is more formally given as “Mi’kmaq,” which comes from a word meaning “my friends,” aptly befitting the gregarious Dennie Meuse, whom the Boston Globe, in 1909, described as “one of the jolliest [Indians] that ever lived.” Born in 1861 as the direct descendant of Native American chieftains in Nova Scotia, he moved to East Milton in 1888. Returning for a visit there in 1890, he happily brought back to East Milton with him Mary Hannah Gload, “the prettiest squaw of his tribe,” who had become Mrs. Meuse. The Meuses’ “exceedingly comfortable house,” said the Globe, was “situated in one of the wild spots among the granite quarries on the line between Milton and West Quincy.” There they raised a son, born in 1898, who in baptism was given the curiously Irish names of Dennis Scanlon Paul. (The Meuses were devout Catholics, and Dennie in fact hiked across the rocky quarries early every morning to attend Mass at St. Mary’s in West Quincy – well before St. Agatha’s parish existed. Hence, since in their day they would have strictly observed Church law to give children names of saints, we surmise that their son’s middle name of Scanlon may have been for a pious priest the Meuses had known.) Behind their East Milton home, said the Globe, “the ground slopes sharply down to a rough valley, where there is a spring of pure water, which Dennie says used to be drunk by great numbers of Indians. He says he knows this by the many ‘signs’.” This was near what Dennie also recognized as a well-defined Indian trail. Hannah wove sweet-grass baskets. Dennie, among other things, sold the baskets and other Indian wares, and also fashioned ax handles – a modest, if somehow adequate means of income for a humble couple. So what, then, prompted the Globe to describe Dennie as “one of the most prominent characters in that town”? For one thing, he was renowned for his extraordinary strength. According to the Globe, “people who know him say that when he makes a slip in shaving ax handles . . . he will often, with an impatient grunt, simply draw his hands together, snapping the tough ash handle as if it were a straw.” But there was much more compelling reason for his local notoriety. Every summer the Meuses would mysteriously disappear for two months. It wasn’t until Milton Police Chief Maurice Pierce happened to visit Nantasket Beach that the mystery was solved. There Pierce discovered our resident Micmac “in the

act of doing his star performance – picking an apple from his wife’s head, aiming over his shoulder with the aid of a mirror.” For, Dennie was an expert marksman with a rifle who used to perform “hair raising” shooting stunts at resort areas each summer. “Oh yes,” he told the Globe, “I can do all sorts of things with the rifle. I used to shoot cigars from my wife’s mouth, used to shoot apples apart from between her fingers and apples from her head.” When the reporter asked Hannah if she was afraid to be shot at, “she smiled in genuine astonishment. ‘Why, no,’ she said, ‘Dennie can shoot’.” As of 1909, however, 44-year-old Dennie had retired the celebrated sharp-shooting act. “[T]his past year I came awfully near hitting her. You can’t depend on the cartridges they make nowadays. I love my wife and I’m not ready to part with her, so there will be no more shooting.” In reality, it was Hannah who would have to part with Dennie only a few years later. On February 13, 1915, he succumbed to septicemia in his home off Granite Avenue, and was buried in Milton Cemetery. A few years later, we find Hannah living at 46 Granite Avenue near Squantum Street (an address later displaced by the Southeast Expressway) until 1921, when she moved into “Camp Oakwood,” a modest, yet elegant hilltop house off Randolph Avenue. Mary Hannah Meuse passed away in 1925, survived by the younger Dennie and a daughter named Margaret who, after graduating from Milton High School in 1924, worked at the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. In 1926, son Dennie was listed as living at 122 Pleasant Street. After 1929 there was no further mention of any member of the Meuse Family in town. With that, therefore, the sometimes vivid, but most often veiled and inscrutable record of Indians in Milton quietly, unceremoniously fades away. No, there are no Native American “wigwams” to be found anywhere in the town. Even the Indian pits are now gone. But who knows? Maybe – just maybe – a little scratching into the soil around the Blue Hills to the west, or by the quarries near East Milton, can still unearth an old arrowhead.

|

The Ponkapoags were a local tribe, most of its members dwelling in the Canton and Stoughton area. One of the last full-blooded Ponkapoags was Daniel Crowd. We have scant information about him, beyond the fact that he had married an African American lady named Betsey Digans, and that they had a daughter, Mary Emeline. In 1860, the family moved from Canton to Milton, settling in “Blue Hill Village” at the corner of Canton Avenue and Harland Street, not far from where Mingo once had lived. Mary married a stone mason named George, who had the same surname of Crowd. George J. Crowd died in 1879 at age 56, and so Mary earned “a little money by boarding colored foundlings, wards of the state.” She also would substitute for vacationing governesses. In his book, Family Jottings, Roger Wolcott hinted at her charms with children by reminiscing on how “She had a number of songs for our entertainment.” And she also “was well remembered by older Stoughtonians as being able to ‘fix a skunk for eating’.”

The Ponkapoags were a local tribe, most of its members dwelling in the Canton and Stoughton area. One of the last full-blooded Ponkapoags was Daniel Crowd. We have scant information about him, beyond the fact that he had married an African American lady named Betsey Digans, and that they had a daughter, Mary Emeline. In 1860, the family moved from Canton to Milton, settling in “Blue Hill Village” at the corner of Canton Avenue and Harland Street, not far from where Mingo once had lived. Mary married a stone mason named George, who had the same surname of Crowd. George J. Crowd died in 1879 at age 56, and so Mary earned “a little money by boarding colored foundlings, wards of the state.” She also would substitute for vacationing governesses. In his book, Family Jottings, Roger Wolcott hinted at her charms with children by reminiscing on how “She had a number of songs for our entertainment.” And she also “was well remembered by older Stoughtonians as being able to ‘fix a skunk for eating’.”  Last not Least

Last not Least