Famous Miltonians

Milton’s Legacy

Influential Figures Who Shaped History

Throughout its history, Milton, Massachusetts, has been home to a remarkable group of individuals who have left their mark on the nation and beyond. From political leaders to literary figures, business magnates to scientific pioneers, these notable figures have shaped industries, influenced policies, and contributed to society in meaningful ways. Whether born in Milton, educated here, or drawn to the town’s rich history and distinguished institutions, here are just a few individuals who have helped tell the story of Milton’s lasting impact.

-

One of the most celebrated poets of the 20th century, T. S. Eliot was a student at Milton Academy. His time in Milton contributed to his early academic foundation before he went on to achieve international literary acclaim with works such as The Waste Land and The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.

-

A railroad magnate, merchant, philanthropist, and abolitionist, John Murray Forbes played a major role in the expansion of American railroads. He lived in Milton, where he also became known for his dedication to philanthropy and his staunch opposition to slavery, supporting abolitionist causes during the Civil War.

-

A pioneering neurophysiologist from Milton, Alexander Forbes made significant contributions to the study of the nervous system. His research played a key role in advancing the field of electrophysiology and medical science.

-

A sea captain, China merchant, shipowner, and writer, Robert Bennet Forbes was deeply involved in maritime trade. Raised in Milton, he played a significant role in the opium trade with China and later advocated for naval reform in the United States. Captain Forbes built a Greek Revival mansion on Milton Hill in 1883, which is open to the public as the Forbes House Museum and listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

-

The former Governor of Massachusetts (2007–2015) attended Milton Academy before embarking on a distinguished career in law, business, and public service. His time at Milton Academy helped shape his leadership and advocacy for civil rights and economic development.

-

Henry Endicott Stebbins (1905-1973), son of Rev. Roderick Stebbins and Edith Endicott (Marean) Stebbins, was born in Milton, Massachusetts, educated at Milton Academy, and a member of Harvard Class of 1927.

Stebbins entered the Department of State as Foreign Service Officer of Class 8 on July 1, 1939. After serving in various posts in Europe and Turkey, Stebbins was named Vice Consul in London under Joseph P. Kennedy in 1939. He became First Secretary of the London Embassy in 1945 during which time he met his wife Barbara Jennifer Worthington, a native of Dorset, England. In 1951 he was named Consul at Melbourne, Australia. Four years later President Eisenhower promoted him to Foreign Service Inspector, naming him Senior Inspector a year later. In 1959 Eisenhower named Stebbins the first Ambassador to Nepal where he served until 1966. Read further below.

-

Elbie was an American professional baseball first baseman. He played all or part of 12 seasons in Major League Baseball for the Boston Braves (1934–35) and Bees (1937–39), Pittsburgh Pirates (1939–43, 1946–47) and Braves again (1949). Fletcher batted and threw left-handed.

Fletcher made his major league debut in 1934 in an unusual way. A contest was held to determine which Boston-area high school player was most likely to reach the major leagues, with the winner receiving an invitation to the Braves' spring training camp. With the help of a number of votes from his large family, Fletcher won, and then actually made the team. Read more below.

-

Edward Allen "Eddie" Gisburne was a United States Navy officer and a recipient of the U.S. military's highest decoration, the Medal of Honor, for his role in the battle which began the U.S. occupation of Veracruz, Mexico. He earned the medal as an enlisted man for ignoring heavy fire and his own severe injuries to drag a wounded marine to safety. Although he lost his left leg in the fight, he went on to complete two more terms of service with the Navy, one as a radio operator during World War I and another as a 50-year-old commissioned officer in World War II. Read more below.

-

Read about George Thompson’s story below.

Milton’s history is enriched by the accomplishments of these notable individuals, whose work continues to shape politics, literature, business, science, and society. Their ties to the town underscore its tradition of fostering leaders, thinkers, and innovators who leave a lasting legacy.

Ambassador Henry Endicott Stebbins (1905-1973)

Henry Endicott Stebbins (1905-1973), son of Rev. Roderick Stebbins and Edith Endicott (Marean) Stebbins, was born in Milton, Massachusetts, educated at Milton Academy, and a member of Harvard Class of 1927.

Stebbins entered the Department of State as Foreign Service Officer of Class 8 on July 1, 1939. After serving in various posts in Europe and Turkey, Stebbins was named Vice Consul in London under Joseph P. Kennedy in 1939. He became First Secretary of the London Embassy in 1945 during which time he met his wife Barbara Jennifer Worthington, a native of Dorset, England. In 1951 he was named Consul at Melbourne, Australia. Four years later President Eisenhower promoted him to Foreign Service Inspector, naming him Senior Inspector a year later. In 1959 Eisenhower named Stebbins the first Ambassador to Nepal where he served until 1966.

The United States Educational Foundation in Nepal was established by Ambassador Stebbins and Education Minister Vishwa Bandhu Thapa in 1961 to promote a “mutual understanding between the peoples of the United States of America and Nepal by a wider exchange of knowledge and professional talents through educational activities.”

Mrs. Stebbins, who was active in social welfare and various women’s organizations in both Nepal and Uganda, said “To make the most of a life like mine you must also enjoy your husband’s job and enjoy people.” She believed that an understanding of the life and problems of women in other countries could help strengthen international goodwill and friendship. Mrs. Stebbins became conversant in the Nepalese language, spending time encouraging school children.

When named as Ambassador to Uganda by President Johnson in 1966 Stebbins’ 89 year old mother on hearing of his appointment was “thrilled” at the news. “But I’d rather he was a street sweeper in

Milton” she added. “He’d at least be home, then.” Three years later, retiring from the Foreign Service, Henry finally came ‘home’ to Milton.

Tragically on March 28, 1973 Ambassador Stebbins was lost at sea after an apparent fall from the deck of the S. S. Leonardo da Vinci.

A chautaro or ‘resting place’ memorial was constructed in his memory at a cost of 25 hundred rupees, donated by the first group of Peace Corps volunteers working in Nepal.

Ambassador & Mrs. Stebbins greet Queen Elizabeth – Nepal 1961

Elbie Fletcher,

Major Leaguer of Otis Street

From the Milton Historical Society’s Fall 2006 Newsletter.

By William P. Fall

By this time every year, what was once America's favorite pastime becomes so once again. At least for the season’s balance.

And while, ordinarily, baseball in and of itself may not be a leading interest to local historical societies, one of its "boys of summer" is of particular interest to ours – this particular "boy," Elburt Preston Fletcher, having been a Milton native.

It's not that Milton hasn't had its share of sports celebrities. Among those who once called Milton home were: George Owen, of the Boston Bruins; Carl Lindquist, Carl Erskine, and one-time Most Valuable Player for the National League Bob Elliot, all of them members of the Braves (when still a Boston franchise); and, of course, the colorful pitching ace, Luis Tiant, who came to the Red Sox in 1971. But only one was a homegrown, lifetime resident: "Elbie" Fletcher.

And so, with Boston's sole surviving baseball franchise once again having tantalized us late in the season with rising, and then falling, hopes for another world championship, we thought that as a change of pace we would introduce – or, as the case may be, re-introduce – to his fellow townsfolk the once-prominent baseball figure, who lived for so many years at 131 Otis Street – up the street from this writer.

_________

Girls, we were incessantly reminded as kids, are made of "sugar and spice and everything nice." While as for boys, well....

For one thing, boys are natural-born tellers of tales. This is because prevaricating mildly (or not so mildly) is just part of their innate boastful make-up — which for some is never fully outgrown. Since bragging itself happens to be a competitive sport with boys, garnishing self-aggrandizing claims with exaggerations, slight or substantial, is, for all intents and purposes, an essential ingredient to boyhood. (It’s almost as if they were granted a special fibbing indulgence by the Pope, who, after all, must have been a boy himself once.)

So it was that when we were kids, my Dedham cousin, Billy Barker, used to tell all his Dedham buddies that his Milton relatives live “right next door” to Boston Braves first baseman, Elbie Fletcher, and are such “close friends” of Elbie’s that they – we – could get Cousin Billy tickets to Braves games anytime he'd like. Best seats in the house, too. And, of course, all the autographed baseballs he wanted – from Elbie, Warren Spahn, Johnny Sain, Ted Williams, or any baseball great from either league!

Truth be told, my family lived toward the opposite end of Otis Street from the Fletchers. My siblings and I were only casually acquainted with the Fletcher boys, Bobby and Steve. And none of us, I’m rather sure, had actually met their father directly. So we certainly weren’t on any kind of free-tickets, anyone’s-autograph basis. In fact, none of us then was really even a baseball fan, and thus had little motivation for exaggerated boasts about our not-so-close neighbor – unlike our youthful Dedham kinsman, the world’s most avid baseball fan – ever.

Nevertheless, we were all fully aware that a major league ballplayer lived up the street. And, speaking for myself, even not knowing much about that player or his sport in those days, I suppose I was just a smidgen envious of the bragging rights that legitimately fell to Elbie’s two sons. These would include such impressive facts about their celebrity dad as the following:

While not a Hall of Famer, he nonetheless was recognized as one of the game’s finer players, having once been listed 15th among baseball’s all-time best lead-off hitters (even though Elbie’s oldest son, Bob, questions whether his dad, being a slow runner, ever hit in the lead-off spot). One source ranked him 33rd among the greatest all-time first basemen. Furthermore, he led the National League in on-base percentages for three straight years (1940-42), and for two consecutive years (1940-41) in base-on-balls.

Fletcher once hit an inside-the-park grand slam home run, and twice helped execute a triple play – two of baseball’s rarer feats. And he once played in an All Star game. Little wonder that, Hall of Famer or not, one of Elbie’s baseball mitts not long ago fetched $700 in auction.

Born March 18, 1916, Elbie Fletcher grew up just off of Blue Hills Parkway. On an adjoining street lived a pretty young girl with whom, relates son Bob, the future professional ballplayer became smitten at the age of 14. The girl’s name was Martha Bette Hanson, who somewhere along the way acquired the nickname “Busy.” Hers and Elbie’s youthful romance, in storybook fashion, would last a lifetime, and the two were definitely an “item” by high school. The Unquity Echo yearbook for 1934 describes Miss Hanson as “One of our most attractive and popular young ladies. ’Busy’ is . . . versatile, charming and vivacious, [and] she goes hand-in-hand with our St. Petersburg Romeo” — an indirect reference to Elbie’s already having played two games with the Braves (then called the Boston Bees) while still in high school.

The yearbook remarks of young Fletcher himself: “The popular favorite of Milton High has made the name ‘Elbie’ known with all the athletics of Milton High; and even if he is ‘a one gal guy’ it doesn’t stop other hearts from fluttering as he smiles broadly at everyone.”

Indeed, besides being captain of the baseball team, he was active in football and basketball. But this was no “dumb jock,” as the expression goes. An honor student, Elburt P. Fletcher was: a member of the French Club, Glee Club and Chorus; was president of the Mathematics Club and Athletics Association; and was class president.

Making his major league debut with the Boston Braves at age 18, Elbie was described as “a flashy fielding, line drive hitting first baseman” who “displayed top fielding range with an excellent batting eye.” Another writer remarked, concerning his acquisition: “The Braves seemed to have a knack for finding local talent which the Red Sox somehow overlooked.”

This was the same year that aging baseball legend, Babe Ruth, having been dropped by the Yankees, was picked up by the Braves mainly for his marquee name. “We were all awed by his presence,” said Fletcher. “He still had that marvelous swing, and what a beautiful follow-through! But he was 40 years old. He couldn’t hit the way he used to. It was sad watching those great skills fade away.”

But Ruth’s fading glory wasn’t the team’s only problem that year. Despite having a flashy first baseman from Milton, the 1935 Braves were just awful, having gained the dubious distinction of being second worst team in major league history, by finishing the season an abysmal 60 games out of first place! They needed to start rebuilding.

In 1939, Fletcher was traded to the Pirates. While in Pittsburgh he rented his Otis Street home to famed power hitter, Bob Elliot, the National League’s 1947 MVP who retired with the highest slugging average (.440) for a third-basemen in all of professional baseball. (Imagine what my Dedham cousin might have made of that, had he only known!) Elbie’s career really took off with the Pirates, becoming an outstanding hitter over the next four years, and earning a starting spot on the NL’s 1943 All Star game lineup. Drafted into military service that same year, he returned in 1946 to resume playing for Pittsburgh. Like the Babe, with whom he had spent his rooky year, however, Fletcher’s own skills were soon fading. In 1949, he came back to the Braves, playing alongside “pray for rain” pitchers Spahn and Sain, but quietly finished his professional career that season back home in Boston.

In retirement he coached the Little League team sponsored by his next-door neighbor’s business, Cole & Gleason Funeral Home. And for several years he served as the Melrose Park Commisioner. On March 9, 1994, Elburt Preston “Elbie” Fletcher, the former “slick-fielding, left-handed first baseman who excelled at hitting line drives and getting on base,” passed away in Milton, the town he had called home all his life.

Don’t worry about sounding professional. Sounds like you. There are over 1.5 billion websites out there, but your story is what’s going to separate this one from the rest.

Edward A. Gisburne

A Hero for Heroes,

Milton’s Edward A. Gisburne

By William P. Fall

From the Spring 2007 Newsletter

Nailed beneath the basement staircase in this writer’s home is a welcome sign, artfully traced out on white cardboard, with polychrome embellishment, reflecting the thoughtfulness of its creator. It was put there in 1942 by the departing occupant for my incoming family. Though then not yet a member of the family, I have been no less proud or gratified than they that the sign has been reverentially preserved, in the same exact spot, for 65 years now. The reason is that its maker, our home's first owner, was Edward Allen Gisburne — Congressional Medal of Honor recipient.

There is no higher honor than the Congressional Medal of Honor, awarded for distinguished valor in action against an enemy force. Only two CMOH recipients are buried in Milton Cemetery: The other, besides Edward “Eddie” Gisburne, is a German-born Milton resident named Paul Weinert, who so distinguished himself in battle at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, as to merit this coveted medal. To deny nothing of Weinert’s unquestionable bravery in 1890, however, it should also be realized that the standards of heroism in awarding the medal had been set even higher by Gisburne's time.

But what distinguished Eddie Gisburne as even more extraordinary amongst America's most extraordinary heroes, were commendable contributions he made for his country after already having received his Medal of Honor for bravery.

In a piece penned for the May 17, 1942 Boston Sunday Post,* writer and artist Bob Coyne described the “breathless hush” that had hung over our country in 1917, before America’s entry into World War I then raging in Europe. At recruiting stations, Coyne said, there were “long lines of young men eager to go over there, to fight in a great cause. Among those waiting at one Boston station was a young man: he was tall and well-built, but he had only one leg.”

The one-legged lad was 21-year-old Edward A. Gisburne. And some of the enlistees waiting in the queue could only smile at his magnanimous spirit, thinking that no one with so serious a physical impairment, after all, could really expect he may be considered for military assignment. But when Gisburne presented himself to the recruiting officer, Coyne continued, “those who had been amused were amazed at what followed. The officer, noting a medal in Gisburne's lapel, rose to his feet.

“‘It is a rare occurrence to meet one who has merited the Congressional Medal of Honor,’ he said. ‘You are probably one of the youngest to have ever received it. And I consider it a privilege to greet you.’ In this way Gisburne re-entered the U.S. Navy.”

One may better appreciate the immense esteem that lay behind the recruiter’s greeting, by knowing that President Harry Truman once told a Congressional Medal of Honor recipient: “I would rather have this medal than be President of the United States.” And, in light of his own profound respect, General George S. Patton might be forgiven for his characteristically excessive exuberance in having once said: “I would give my immortal soul to receive the Medal of Honor.”

Of course, not even a Congressional Medal of Honor would be enough to earn admission into active duty with a missing leg. Eddie Gisburne first had to get a waiver directly from Secretary of War Daniels himself.

Preamble to Valor

Eddie had been born in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1892, but received his early education in the Quincy schools, and in Washington, D.C. At age 18, months before the Great War in Europe had broken out, his first enlistment in the Navy brought him into the little-remembered tempest at Vera Cruz during one of the many revolutionary upheavals that gripped Mexico spanning across two centuries. Francisco Madero, who had been elected President of Mexico by the largest margin of the popular vote to that time, was overthrown and murdered by a thug named Gen. Victoriano Huerta, described as "a drunkard and repressive dictator . . . almost too bad to be true."

In April 1914, a supply boat from the U.S.S. Dolphin, in Mexican waters on a diplomatic mission, was seized by Huerta's henchmen, and its crew arrested and paraded through the streets as a gesture of deliberate insult and provocation against the United States government. Even after Huerta's regime flatly refused to apologize for the incident, President Woodrow Wilson responded with bewildering restraint, telling Congress: "There can in what we do be no thought of aggression"! Congress emphatically disagreed, and authorized sending marines into Vera Cruz. Carrying the forces that would subdue the city after three days of fierce battle, which began on April 21, were three Navy vessels: the Prairie, the Utah, and the Florida. Electrician Third Class Eddie Gisburne was aboard the latter ship.

Once a Hero . . .

In the course of the battle, according to Bob Coyne’s account, and under intense fire, Gisburne made his way to the roof of the Terminal Hotel, presumably to set up radio contact. With him on the rooftop was a marine from Cambridge whose name was Haggerty.

“So heavy was the beating of bullets that Gisburne was knocked down,” wrote Coyne. “As he rose to his feet, he saw Haggerty slump and fall so that part of his body dropped beyond the edge of the roof. . . . Without thought of [the] heavy fire he rushed toward the wounded marine. But Rebels had the place spotted. Bullets seemed to be all about him and he pitched forward. The roar in his ears was so terrific that it seemed as though worlds were tumbling about him and pains stabbed his body.

“It was an ugly sight and of course especially painful, but Gisburne ignored his own great need. Close by was one whose need was greater. Somehow Gisburne dragged himself the short distance; but even that effort almost cost his life. It took his last ounce of strength and his hands, from which the flesh had been torn, showed how much those few feet cost.

“Gasping with pain, he reached Haggerty. The marine was torn with bullets, yet when Gisburne dragged his broken body from its perilous position, there was a quiver of recognition in those almost sightless eyes as though he [Haggerty] were grateful. Out of the path of fire, Gisburne dragged the wounded man into a shelter on the roof.

“For a few moments Haggerty rested quietly in Gisburne's arms and then as though he were weary he drifted into the mystery and the silence. But even before he had passed, Gisburne slipped into unconsciousness. There they found them: the dead body of a marine at rest in the arms of a blue-jacket who was close to the end himself. Only his indomitable will to live saved him, brought him through, after months of suffering, to face life with only one leg.”

The only remarks young Eddie made after his rescue were: "Haggerty was brave. I saw him shooting it out. He never drew back." He was mute regarding his own selfless heroics. But the Congressional Medal of Honor awarded him by the President of the United States, on June 15th the same year, compensated for young Gisburne’s personal reticence.

Such uncommon bravery, especially at the cost of a limb, would be far more than enough service for one man to his country. As his commanding officer said of him: "He is entitled to every consideration from his countrymen and his country." But, as already indicated by Bob Coyne, it wasn’t enough for Eddie. Since the Civil War, six generations of his family had served in the Navy, so he wasn’t going to let a threeday battle in Mexico and the absence of a leg define his total service. "I couldn't break with tradition," said Gisburne, "I knew there was a place for me." And there was indeed. An expert in radio, he handled all communications of Atlantic cruisers and transports throughout World War I. "Whatever I do, let me do it my way. I am not a cripple," was the personal code he drafted and adopted for life.

One of his fondest memories from that second wartime stint was serving on the transport ship, the George Washington, when it carried President Wilson to Europe.

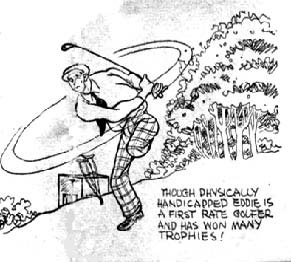

After the war, he returned to civilian life in Milton where, during his 35 years of residence, he and his wife Ena raised their two boys. In succeeding years, he would: teach radio courses at Boston College; serve as a reporter for the Quincy Patriot Ledger; become district manager of Boston Edison; and serve as continuity editor for Radio Station WEEI. He would also hold memberships in the Engineers Club of Boston and the Wollaston Golf Club (where Coyne said he was a “firstrate performer and . . . won many trophies”).

As busy as all those activities must have kept him, however, Ed Gisburne was fervently committed to civic responsibilities. A member of the Milton Town Club and active in town affairs, he was twice elected to the Milton School Committee

– in 1935, running from his duplex residence at 118 Otis Street; then in 1938, from his newly-built home at 36 Otis Street.

Ever a Hero

In May of 1942, Bob Coyne could only bring his article to a close by tentatively observing: “The Gisburnes carry on. A son, Edward, Jr., is an aviation cadet. Friends believe that only armed force will keep Edward, Sr., from once again taking his place in the list of recruits.”

But that was still just five months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Not much later – perhaps shortly after selling his Otis Street home to my parents and moving to upper Waldeck Road – Eddie, Sr. did, in fact, manage to “re-up” once again, despite being not merely an amputee, but now a 50-year-old one! This time, he returned to service as a commissioned Navy lieutenant, and was stationed at Quonset, Rhode Island.

His son John also had entered active service. And the junior Edward Gisburne was serving in the Pacific theater, attached to the 40th Bomb Group.

It was July 21, 1945, when the Milton Record sadly announced: “Word has been received by Lt. and Mrs. Edward A. Gisburne of 80 Waldeck Road, that their son, S. Sgt. Edward A Gisburne Jr., was reported missing in action May 26, while on an air mission. . . . He had been awarded the Air Medal for outstanding performance in serial combat against the Japanese.” The tragic outcome of that nightmare was that the Gisburne’s eldest son, at age 29, had in fact been killed in action in his B-29.

In 1950, the couple relocated to Duxbury. And on August 29, 1955, Eddie, Sr. himself, passed away, at age 63, at the Chelsea Naval Hospital.

God alone can properly reward the sacrifices of life and limb and model commitment rendered by the Gisburne Family – and especially by Eddie, who lost not only his leg but his decorated son in service to his country – and who not only performed with exemplary valor in one war, but served admirably in two world conflagrations after that.

* * *

Bronze plaque at Gisburne’s grave.

Towards the rear of Milton Cemetery, just off Circle Avenue, with two strong oaks symbolically standing close by, can be found the Gisburne family plot. It contains graves for Eddie, his wife Ena, and their son Edward, Jr. — though the remains of the latter actually were never recovered.

It is heartwarming to see the son’s name included on memorials, in both the Town Hall and the Central Library, that commemorate our town’s war dead.

A bronze plaque has been added to the father’s grave as well. But certainly more than merely a small plaque is due — from Milton and from all of American society — to honor a man of such remarkable bravery, sacrifice, and service to his country far above and beyond the call of duty.

Is it unreasonable to think that monuments ought to be erected for him? That streets, parks, schools, bridges, public buildings should be named after him? This only seems fitting, since those same kinds of tribute so frequently are lavished on politicians simply for having warmed a seat in some political office.

Now that Milton again is home to a state governor, perhaps at least one such long-overdue, much-deserved honor will finally be accorded this Milton hero, Navy Lt. Edward Allen Gisburne, Congressional Medal of Honor recipient.

In the meantime, a small, very old, cardboard welcome sign still remains nailed to my home’s basement staircase as my family’s own, special little monument that for us says: “A Very Great Man Once Lived Here."

___________________

* Coyne's piece, titled "Courage in the Crisis," is the source for much of the material about events at Vera Cruz referenced in this article. As its writer, I am confident of the general factual accuracy of Coyne's material, since he clearly had to have gotten it directly from Edward Gisburne by personal interview. Gisburne, in fact, left a copy of the Coyne article in the Otis Street house that my parents bought from him, which itself further tends to indicate that it had met his approval..WPF

A Local Friend and an International Hero

Probably none of the hundreds of guests who have visited the Suffolk Resolves House annually, on the occasion of its September Open House, have had any notion that the venerable gentleman, always on hand to greet them in his Daniel Vose period costume with a three-cornered hat and buckled shoes, was a war hero. And a very exceptional one at that. We think none knew this about Milton's George Thompson — longtime member of our Historical Society and longer-time spouse of our Board Member, Anne Thompson — because none of us, save Anne, even knew about it!

On November 6th, 2007, our already decorated war hero, along with six other World War II veterans of the Normandy Invasion, received France's highest award, the Legion of Honor, from French President Nicolas Sarkozy, at a reception at the French Ambassador's Residence, in Washington, D.C. We in the Milton Historical Society are enormously proud of our dear friend and member, George Thompson, as should all of Milton be of their honored neighbor, as well. And so, we are most pleased to provide the following article, with permission, about the event from the Boston Globe.

France honors humble veterans

By David Abel

Globe Staff / November 6, 2007

MILTON - Nearly every morning since World War II, George M. Thompson has walked outside his two-bedroom townhouse to hang a US flag over his driveway. Before sunset, the 82-year-old Army veteran takes the flag inside, a ritual that he says has helped him hold on to memories of the fellow soldiers he watched die between the beaches of Normandy and the Battle of the Bulge.

Sixty-two years after completing their mission, Thompson and six other veterans who helped liberate France will today be awarded the Legion of Honor, France's highest award. President Nicolas Sarkozy, who has sought improved relations with the United States since being elected in May, will present medals to the men in Washington, where tomorrow he will address a joint session of Congress.

Thompson says he is honored but doesn't feel worthy.

"I don't think I was a hero," he said at his home yesterday before officials from the French consulate arrived to escort him to the airport. "I did nothing different than another 100,000 people. The true honor is that I'm alive to get it - that I survived."

Thousands of Americans have been made knights in the order of the Legion of Honor, which Napoleon Bonaparte founded in 1802 to recognize the exploits of great artists, scientists, and soldiers, among others. Thompson joins Americans such as Presidents Dwight Eisenhower and Ronald Reagan, Generals George Patton and Norman Schwarzkopf, and artists Martin Scorcese and Edith Wharton.

Alexis Berthier, a spokesman for the French consulate in Boston, said Thompson and the other men were chosen for their bravery. He said the French government had been considering honoring the men over the past year but expedited its review of their records to allow Sarkozy to award them their medals.

"We look for those who have really distinguished themselves," Berthier said.

The Legion of Honor is one of several medals that Thompson has received for his 18 months in combat.

He earned a Purple Heart after he was wounded in the Battle of Chambois and a Bronze Star for his bravery while helping others cross the Moselle River, which runs through France and Germany. He also has ribbons for fighting in five major battles, which took him as far as Pilsen, Czechoslovakia, where he was attached to the 359th Regiment of the 90th Infantry Division.

Not long after, he said, he was part of the occupying force in Germany, living in German barracks, where local nuns ironed his underwear and socks.

Joining Thompson in Washington today will be Charles N. Shay, 83, of Old Town, Maine, a combat medic who served in the First Division, landed on Omaha Beach on D-day, and spent six weeks as a prisoner of war. A Penobscot Indian whose ancestors were allies of George Washington during the Revolutionary War, Shay received a Silver Star and four Bronze Stars.

In a phone interview shortly before he left for Washington, Shay said he saw the award as a way to honor the Penobscot nation.

"It's an honor for me, but it's a great honor for my people," he said.

The award was also an honor for Thompson's and Shay's families.

Thompson's wife, Anne, yesterday wore a Joan of Arc ring and a shawl decorated with American flags. "He's very modest," she said, "but I couldn't be more proud of him."

Thompson, who helped build nuclear submarines and served in local government after the war, has three daughters and eight grandchildren, all of whom were en route yesterday to Washington.

"We're just speechless," said Kara Russo, one of his daughters, while driving to Washington. "I'm in awe of him and what he has done."

Her 15-year-old daughter, Rachel, who is in Milton's French immersion program, said she plans to address Sarkozy in French.

"I want to tell him that I'm happy he's giving my grandfather this award," she said. "I was always proud that he was my grandfather, but I'm really proud that he helped free France."

Thompson prepared for the trip yesterday by wearing an old tie covered with American flags and "1976," the nation's bicentennial year.

He also showed off flags he keeps in his basement, including one representing a company that fought in the Revolutionary War. Another he takes out on Memorial Day and Veterans Day, and a third he bought for the turn of the millennium.

"Someone had to be watching over me," he said. "All I can say is that I'm very lucky."

The Governors of Milton

by Anthony M. Sammarco

(from the Winter 2010 Newsletter)

Milton has been an independent town since 1662 when it was incorporated by the Great and General Court and set off from Dorchester. It has had six residents or tax payers who were appointed or elected to serve as governors of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the Province of New England, the Royal Colony of New England or the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Today, the Governor of Massachusetts is the chief executive, and executive magistrate, of the Commonwealth and currently resides in Milton. He, like most other state officers, senators, and representatives, was originally elected annually, however in 1918 this was changed to a two-year term, and since 1966 the office of governor has carried a four-year term. The Governor of Massachusetts does not receive an official residence, or housing allowance. The governor also serves as Commander-in-Chief of the Commonwealth's armed forces. Among our fellow Miltonians who served in the highest elected position are:

William Stoughton (1631-1701) was a landowner on Milton Hill who bequeathed to the town of Milton a tract of land to be used to support the poor of the town. This later became known as the Town Farm and is located at the end of Governor Stoughton Lane. Stoughton was graduated from Harvard College in 1650 with a degree in theology. He intended to become a minister and continued his studies at New College, Oxford, graduating with an M.A. in Theology in 1652. Stoughton was in charge of what has come to be known as the Salem Witch Trials, first as the Chief Justice of the Special Court in 1692, and then as the Chief Justice of the Superior Court of Judicature in 1693. Stoughton was governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay from 1694 to 1699, while still serving as Chief Justice, and again from 1700 to 1701. He was an able and adroit politician who managed the Colony's politics using the power of his governorship and judgeship and appointments to both his council and to lower courts. Stoughton Hall at Harvard College was named after Stoughton, who left a large bequest upon his death. In 1726 the town of Stoughton, Massachusetts was named in his honor.

Jonathan Belcher (1682-1757) kept a summer estate in Milton, at what is today the area of Adams Street and Governor Belcher Lane. He was graduated from Harvard College. In 1718, Belcher was elected to the Massachusetts Council and became colonial governor of Massachusetts and New Hampshire when his predecessor, William Tailer, died. Initially supported by the people of Massachusetts, his popularity dramatically decreased when he brought the censure of the English government upon the colony. He left Massachusetts Bay Colony and was appointed governor of the province of New Jersey where he assisted in the founding of Princeton University, including building the library for the new school. Belchertown, Massachusetts, was named for him.

Thomas Hutchinson (1711-1780) kept a large estate at the crest of Milton Hill that he initially used as a summer house known as “Unquety,” which after 1765 became his principal residence. Graduated from Harvard College in 1727, he became a wealthy merchant. In 1769, upon the resignation of Governor Francis Bernard, he became acting Governor, serving in that capacity at the time of the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770, when popular clamor compelled him to order the removal of the troops from Boston. In March 1771, he received his commission as Governor, and was to be the last civilian governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony. His administration, controlled completely by the British ministry, increased the friction with the patriots. The publication, in 1773, of some letters on colonial affairs written by Hutchinson aroused public indignation. The resistance of the colonials led the ministry to see the necessity for stronger measures. A temporary suspension of the civil government followed, and General Gage was appointed military governor in April 1774. Hutchinson left Massachusetts in 1774 and broken in health and spirit, he spent the rest of his life an exile in England.

Roger Wolcott (1847-1900) was the son of Joshua Huntington and Cornelia Frothingham Wolcott and lived on Home Farm, on upper Canton Avenue. Wolcott was graduated from Harvard University in 1870 and from the Harvard Law School in 1874. He served in the Massachusetts General Court from 1881-1884, and as Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts from 1892-1896. He became governor in 1896 as a result of the death of Frederic T. Greenhalge and served in that position until 1900. The trustees of Milton Academy named a dormitory after Governor Wolcott after his death in 1900.

Deval Laurdine Patrick (born 1956) is the present governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Patrick was graduated from Milton Academy in 1974 and from Harvard University in 1978 and the Harvard Law School. He spent a year working with the United Nations in Africa. Patrick served as United States Assistant Attorney General under the President William Jefferson Clinton serving the head of the Civil Rights Division. Patrick worked on issues including racial profiling, police misconduct, fair lending enforcement, human trafficking, prosecution of hate crimes, abortion clinic violence and discrimination based on gender and disability. He and his wife Diane Bemus Patrick lived on Hinckley Road in the Columbines neighborhood of Milton.